BY

|

Company Tax Rate Australia 2025–26: Complete Guide

Company tax in Australia is a tax your business pays on its profit – that is, your total income minus allowable business expenses.

Taxes on company profits are a major consideration for businesses operating in Australia, and company tax is a key part of the Australian taxation system. Understanding your corporate tax rate obligations is essential for all businesses.

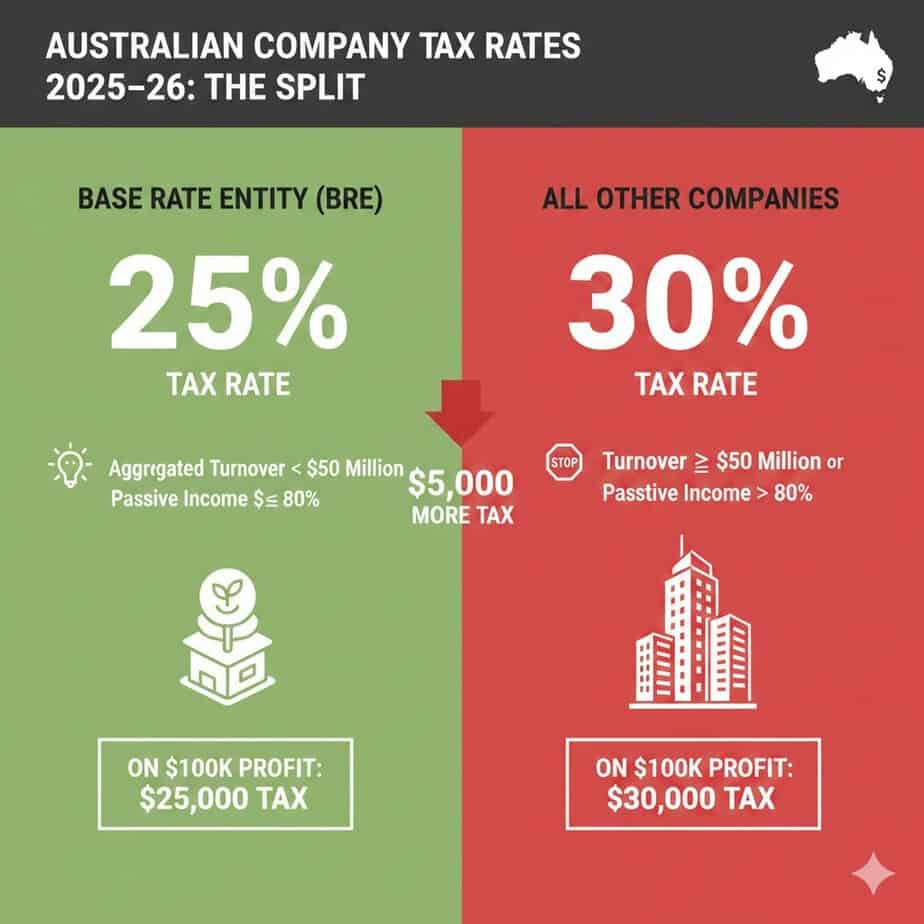

For 2025–26, there are two main Australian company tax rates: the full rate of 30% and the lower rate of 25% for eligible companies. Eligible companies, known as base rate entities, pay the lower company tax rate of 25%, while all others pay the full company tax rate of 30%.

If your company earns $100,000 in profit and qualifies for the lower rate, your tax bill is $25,000—so every dollar of profit is taxed at either 25 or 30 cents, depending on your rate. At the 30% rate, the same profit costs $30,000 in company tax.

Who Gets What Corporate Tax Rate?

The 25% rate applies to base rate entities – companies that meet the eligibility requirements for the lower tax rate, specifically those with a company’s aggregated turnover below $50 million and 80% or less of assessable income from passive sources such as dividends, interest, rent, royalties and capital gains.

Eligibility requirements for the lower tax rate include both the company’s aggregated turnover and passive income thresholds, and recent legislative changes may affect these criteria.

The 30% rate applies to all other companies, including larger businesses, those with high passive income, and companies that fail either base rate entity test. Different tax rates apply depending on whether a company meets the eligibility requirements.

Eligibility is determined annually based on your company’s actual circumstances for each income year, so that you might qualify for 25% one year but not the next. Understanding which rate applies is crucial for tax planning, as different tax rates can significantly impact business profits.

Example

When Sarah registered her digital marketing agency, she assumed “company tax is always 30%” based on what she’d heard from friends in larger firms. Many business owners make this same mistake, not realising that the tax rate can vary depending on their specific circumstances.

At her first-year-end meeting, her accountant walked her through the base-rate entity tests: turnover of $380,000, zero passive income, and all client service fees. She qualified for 25%.

On $95,000 profit, the difference was $4,750 – enough to hire a part-time contractor for three months or reinvest in new software and training.

The lesson: rates aren’t fixed to your business. They’re recalculated every year based on how your company actually operates. Reviewing your tax position annually is essential to avoid costly mistakes.

What’s Changed for Company Tax Rates in 2025–26

The headline company tax rates remain stable in 2025–26: base rate entities still pay 25%, and all other companies still pay 30%.

Both rates have been locked in since the 2024 25 income year, giving businesses predictability for tax planning and cash flow forecasting. This stability allows companies to expect consistent tax obligations when planning for the future.

The $50 million aggregated turnover threshold has been in place since 2018–19, expanding from $25 million in the year prior. This means more mid-sized companies now qualify for the lower rate, provided they meet the passive income test. Eligibility for the lower rate is assessed based on the previous income year’s figures.

Companies with Australian operations and international links should expect ongoing legislative changes that may affect their tax obligations.

What You Need to Check for 2025–26

Even though the rates haven’t changed, your company’s eligibility might have.

Aggregated turnover growth – If your business grew significantly in 2024–25, check whether you’ve crossed the $50 million mark when you include all connected entities and affiliates.

Passive income changes – Adding investment properties, significant interest income, or restructuring to hold shares in other companies can push passive income above the 80% threshold, which is calculated based on your company’s total assessable income.

Related entity structures – New partnerships, trust arrangements, or corporate groups formed during the year can change your aggregated turnover calculation, even if your company’s individual revenue stayed flat.

Developing a strategy to monitor both turnover and passive income is essential to maintaining eligibility for the small-business tax rate.

Measures That Affect Your Company Tax

While the headline rates are unchanged, several related measures impact how much tax you’ll actually pay in 2025–26. Companies must pay tax at the applicable rate, which depends on factors such as turnover and eligibility for reduced corporate tax rates.

The instant asset write-off has been extended to 30 June 2026 at the $20,000 threshold for businesses with turnover under $10 million. This allows eligible companies to immediately deduct the full cost of assets costing less than $20,000, rather than depreciating them over multiple years, thereby reducing taxable income in the purchase year.

Foreign resident CGT changes took effect from 1 July 2025, increasing withholding tax rates from 12.5% to 15% and removing the previous $750,000 threshold. Australian companies with foreign shareholders or cross-border structures should review whether this affects distributions or capital transactions.

Tax compliance programs have been expanded with nearly $1 billion in additional ATO funding from July 2025, targeting multinational tax avoidance, shadow economy activity, and personal tax non-compliance. This means more scrutiny of company structures, transfer pricing, income reporting, and stricter review of company tax returns – getting your rate and deductions right matters more than ever.

New international tax rules, such as the undertaxed profits rule and income inclusion rule, are being implemented to ensure multinational companies pay their fair share.

Who Actually Pays Company Tax?

One of the most common sources of confusion for new business owners is understanding who actually pays company tax – and how company profits are taxed at the company level before any distributions to shareholders, affecting what ends up in your pocket.

Your Company Is a Separate Legal Person

Under the Corporations Act 2001, your company is a separate legal entity the moment it’s registered with ASIC. This means your company lodges its own tax return, pays tax in its own name, and owns its own assets.

You and your company are not the same taxpayer, even if you’re the sole director and only shareholder.

How Tax Hits at Two Levels

Because the company is separate, paying the corporate tax rate can occur twice on the same underlying profit: once when the company earns it, and again when you receive it personally.

- At the company level: Your company calculates its taxable profit and pays company tax at either 25% or 30%, depending on whether it qualifies as a base rate entity.

- At the personal level: When you take money out of the company – whether as salary, wages, director’s fees, or dividends – you must include it as assessable income in your individual tax return and pay personal tax at your marginal rate.

This is where franking credits come in.

The Base Rate Entity Tests Explained

Whether your company qualifies for the 25% rate comes down to two very specific tests, both of which must be passed in the same income year.

Test 1: Aggregated Turnover Below $50 Million

Your company’s aggregated turnover must be less than $50 million for the income year.

But “aggregated turnover” isn’t just your company’s revenue shown on your profit and loss statement. Aggregated turnover is the sum of your company’s annual turnover plus the annual turnover of any entities connected with your company, plus the annual turnover of any affiliates of your company, minus amounts from transactions between connected entities and affiliates (to avoid double-counting).

For some reporting and eligibility purposes, GST turnover may also be relevant, such as when determining whether your business must lodge monthly Business Activity Statements or meets certain tax obligations.

Connected entities exist where there is a control relationship, typically 40% or more ownership or voting power. This includes Australian or overseas companies, partnerships, trusts, and individuals.

Affiliates are individuals or entities that act, or could reasonably be expected to act, in accordance with your company’s directions or wishes. Spouses and children under 18 are automatically treated as your affiliates for aggregated turnover purposes.

Test 2: Passive Income 80% or Less

No more than 80% of your company’s assessable income can be base rate entity passive income (BREPI).

Base rate entity passive income includes dividends (corporate distributions), interest income, rent and royalties, net capital gains, and certain trust distributions that are passive.

Active business income is excluded from BREPI, including trading revenue from the sale of goods or services, professional fees, construction and contracting income, and manufacturing revenue. Trading income and other forms of corporate income are also excluded from BREPI, as they are considered active rather than passive income for tax purposes.

Example: The Passive Income Trap

Jason runs a consulting business through his company that generates $380,000 in annual fees. Over three years, he gradually adds investment properties to diversify income:

- Year 1: $380,000 consulting, $35,000 rent → 8.4% passive → 25% rate

- Year 2: $410,000 consulting, $95,000 rent → 18.8% passive → 25% rate

- Year 3: $320,000 consulting, $285,000 rent → 47.1% passive → 25% rate

In year 4, Jason semi-retires and cuts consulting to two days per week: $160,000 consulting, $340,000 rent → 68% passive → 25% rate.

But he forgets about a large term deposit that matures mid-year, earning $78,000 interest. His passive income jumps, but he still stays under 80%.

Year 5, Jason fully retires from active consulting: $0 consulting, $365,000 rent, $125,000 dividends, $42,000 interest. Total income: $532,000, all passive = 100%.

His company now pays 30%, costing an extra $26,600 on the same profit level. The shift happened gradually over five years, but the trigger was crossing the 80% line in a single income year.

How to Calculate Your Company Tax Rate

Calculating company tax follows a simple two-step process:

Step 1: Calculate taxable income

Taxable income = Assessable income − Allowable deductions

Step 2: Apply your company’s tax rate

Tax payable = Taxable income × Tax rate (25% or 30%)

Your company’s taxable income is not the same as your profit shown on your management accounts – it’s a tax-adjusted figure that follows ATO rules about what income must be included and what expenses are deductible.

What Counts as Assessable Income?

Assessable income includes all gross income from your business activities: sales of goods or services, professional fees, online sales, foreign income (as resident companies are taxed on their worldwide income), dividends and franking credits, interest earned, rental income, lease payments, compensation payments, government grants, and net capital gains.

What Counts as Allowable Deductions?

To be deductible, an expense must be directly related to earning your business income, not private or capital in nature, and supported by proper records.

Common deductible expenses include employee wages and superannuation, rent and lease payments, utilities, office supplies, software and subscriptions, marketing and advertising, professional fees, business insurance, depreciation of business assets, motor vehicle expenses (business portion only), bank fees and interest on business loans, and repairs and maintenance.

Worked Example: Trading Company Calculation

ProBuild Services Pty Ltd is a construction company that qualifies as a base rate entity:

Assessable income:

- Construction contracts: $1,850,000

- Equipment hire income: $85,000

- Interest on business savings: $12,000

- Insurance claim: $15,000

- Total: $1,962,000

- Employee wages: $680,000

- Superannuation: $74,800

- Materials and supplies: $420,000

- Equipment depreciation: $85,000

- Vehicle expenses: $42,000

- Insurance: $28,000

- Rent: $96,000

- Utilities: $18,000

- Marketing: $22,000

- Accounting and legal: $15,000

- Bank fees and interest: $8,500

- Repairs and maintenance: $32,000

- Total: $1,521,300

Taxable income: $1,962,000 − $1,521,300 = $440,700

BRE status: Aggregated turnover $1.935 million (well under $50 million), passive income $12,000, interest only = 0.6% of assessable income. Qualifies as BRE; pays a 25% rate.

Tax payable: $440,700 × 25% = $110,175

If ProBuild had failed the BRE test and paid 30%, the tax would be $132,210 – a difference of $22,035.

Franking Credits: Bridging Company and Personal Tax

Franking credits (also called imputation credits) are tax credits attached to dividends that represent the company tax already paid on the profits being distributed.

When your company pays tax on its profit and then distributes some of that after-tax profit to shareholders, the franking credits flow through to the shareholders. Shareholders can use these credits to offset their personal tax liability – and if the credits exceed the tax owed, the ATO refunds the difference.

How Franking Credits Are Calculated

The franking credit attached to a dividend depends on the company tax rate your company paid on that profit.

At 30% company rate: Franking credit = Dividend × 0.4286

At 25% company rate: Franking credit = Dividend × 0.3333

Example: Franking Credits in Action

Jenny receives a $700 fully franked dividend from a company that paid 30% tax. Franking credit = $700 × 0.4286 = $300.

Jenny’s tax return includes $700 in dividends and $300 in franking credit, for $1,000 assessable income. At her 30% marginal rate, personal tax is $300. Less than $300 franking credit = $0 net tax payable.

Because Jenny’s personal tax rate matches the company rate, the franking credit exactly offsets her personal tax.

Lodgement Deadlines and PAYG Instalments

Your company must lodge an income tax return for each financial year, even if it made no profit or has a loss. The Australian Taxation Office sets the deadlines and requirements for company tax returns.

- Self-lodged returns: Due 28 February following the end of the financial year.

- Returns lodged through a registered tax agent: Due 15 May (extended deadline).

- Payment due: Typically 1 December for companies with 30 June year-ends.

PAYG Instalments

If your notional tax exceeds $500, or your instalment income exceeds $2 million, the ATO requires quarterly advance payments. Standard quarterly dates are 28 October, 28 February, 28 April, and 28 July.

Missing PAYG instalments triggers automatic penalties and General Interest Charge, even if your actual tax is lower when you lodge.

Late Lodgement Penalties

Failure to lodge penalties start at one penalty unit per 28 days late (currently $313 per period), up to a maximum of five penalty units ($1,565), even if you owe no tax.

Common Costly Mistakes to Avoid

1. Not checking BRE status annually

Assuming last year’s eligibility still applies, it costs $10,000 per $200,000 profit if you pay 30% when eligible for 25%. Small business owners should check their eligibility for small business concessions each year to ensure they qualify for lower tax rates and deductions.

2. Poor record-keeping

Missing $20,000 in legitimate deductions costs $5,000–$6,000 in overpaid tax. Keep all records for 5 years, including the supplier name, amount, date, and nature of the expense.

**3. Not setting aside tax

**Open a separate tax savings account and transfer 25–30% of monthly profit immediately. Don’t wait for year-end surprises.

4. Missing PAYG instalments

Ignoring quarterly notices triggers automatic penalties, even if your actual tax is lower. Companies with listed investment company status have additional compliance considerations regarding PAYG and foreign income reporting.

**5. DIY beyond your complexity

**Engage an accountant when turnover exceeds $300,000–$500,000, you have multiple entities, or you’re unsure about BRE status.

Taking Control of Your Full Company Tax Rate

Review BRE status quarterly – Don’t assume last year’s eligibility still applies. Track passive income percentage throughout the year and review eligibility across multiple income years.

Forecast profit and tax quarterly – Run P&L reports every quarter, calculate estimated tax owing, and compare to PAYG paid, emphasising the importance of paying the correct amount of tax throughout the year.

Optimise deductions before 30 June – Bring forward planned expenses, write off obsolete stock, purchase equipment under $20,000, and ensure super contributions clear by 30 June.

Model your salary/dividend mix annually – Work with your accountant to balance total tax minimisation, super contributions, and borrowing capacity based on your personal goals.

Key Takeaways

- Two rates apply in 2025–26: 25% for base rate entities and 30% for all other companies – eligibility is recalculated annually.

- Both tests must pass: Aggregated turnover under $50 million AND passive income 80% or less to qualify for 25%

- Tax hits twice: Company pays first (25% or 30%), then you pay personal tax on distributions – franking credits offset the personal component

- Set aside 25–30% monthly: Transfer to a separate tax account immediately to avoid year-end cash flow shocks.

- Instant asset write-off continues: Deduct assets under $20,000 immediately for businesses with turnover under $10 million through 30 June 2026

- Proactive planning pays: The difference between reactive compliance and strategic advice is typically $20,000–$50,000+ annually for profitable businesses.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can my company qualify for the 25% rate if we have investment properties?

Yes, but rental income counts as passive income under the base rate entity test. If rental income plus other passive sources exceed 80% of your total assessable income, you’ll pay 30% regardless of turnover. Many property investment companies fall foul of this rule.

What happens if my company changes eligibility during the year?

Your eligibility is determined at the end of the income year based on actual results for that entire year. If you cross the $50 million threshold or exceed 80% passive income at year-end, the 30% rate applies to all profit for that full income year, not just part of it.

Do I need to lodge a return if my company made no profit or had a loss?

Yes, all companies must lodge an annual income tax return regardless of profit or loss. Failing to lodge triggers automatic penalties starting at $313 per 28-day period, even if you owe no tax.

How do franking credits work with the two different rates?

Franking credits are calculated based on the company’s tax rate. At 25%, franking credit = dividend × 0.3333. At 30%, franking credit = dividend × 0.4286. Importantly, franking rates are determined by your previous year’s tax status, not your current year.

What is aggregated turnover, and why does it matter?

Aggregated turnover includes your company’s revenue PLUS the turnover of all connected entities (40%+ control) and affiliates (those acting according to your directions). Many business owners miss this and only count their individual company revenue, which can lead to incorrect BRE eligibility.

Can I change my PAYG instalments if profit changes during the year?

Yes, you can vary PAYG instalments if your business circumstances change significantly. However, if you underestimate and pay too little, you’ll owe General Interest Charge on the shortfall from the original due dates.

Is it better to take a salary or dividends from my company?

It depends on your personal situation. Salary is tax-deductible to the company and builds payslip history for loans, but creates super obligations (11.5% in 2025–26). Dividends carry franking credits but aren’t deductible, and require a 2-year history for bank servicing. Most owners use a strategic combination.

What records do I need to keep for company tax deductions?

Keep all records for a minimum of 5 years,g the supplier name, amount paid, date, and nature of the expense. Missing proper documentation for $20,000 in legitimate deductions costs $5,000–$6,000 in overpaid tax.

When is company tax actually due for payment?

For companies with 30 June year-ends, tax is typically due 1 December following the year-end, regardless of when you lodge your return. Self-lodged returns are due 28 February; returns lodged through a registered tax agent have until 15 May.

What’s the biggest mistake business owners make with company tax?

Not reviewing BRE eligibility annually and assuming last year’s 25% rate still applies. Changes in passive income, business structure, or connected entities can push you into the 30% bracket without warning – costing $10,000+ per $200,000 profit.